A World Without Facebook? Professor’s New Book Explores Social Media’s ‘Prehistory’

In this day of instant online connection, Kevin Driscoll’s story sounds like something out of the Stone Age.

But, yet, it was only during the 1990s when the now-University of Virginia media studies professor used to walk down Main Street in his Massachusetts hometown in search of a sign that said “Internet.”

“I would follow the arrow to an office, where they had a service provider,” Driscoll said. “And that was my first time having full-on access to the internet.”

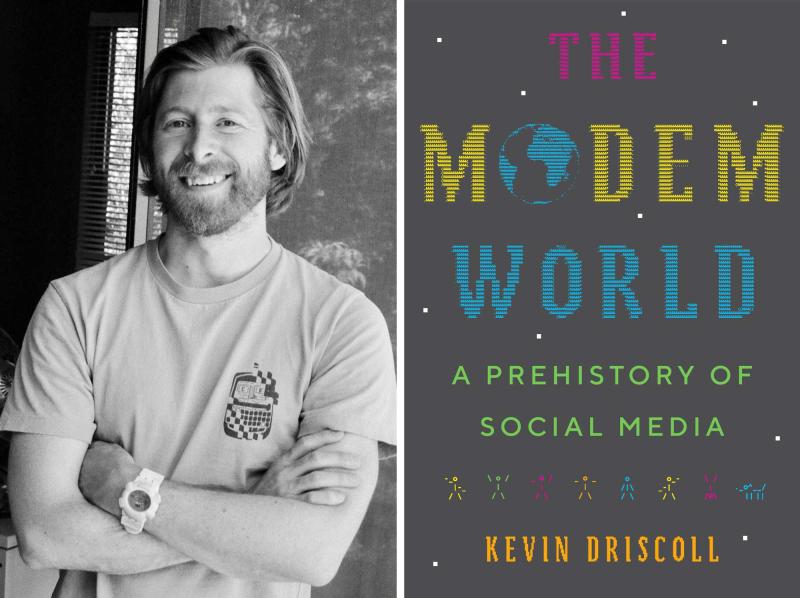

Driscoll’s personal experiences helped launch research into his new book, “The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media,” a dive into what online communication looked like before Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, and the communities of hobbyists, activists and entrepreneurs that were formed.

Driscoll was very much a part of that era.

He grew up going to a local store that created a club for those who liked to play Dungeons & Dragons, a popular fantasy boardgame. At first, Driscoll said, club members could sign up to play on a physical calendar and then go to their assigned tables.

“The people who ran the store then decided to create a dial-up bulletin board system, just like a local online service,” Driscoll said. “You could go on the bulletin board, post messages and play games.”

Driscoll and his friends, however, didn’t have modems at home to connect to the club’s system. They instead went to the store and took turns getting on the computers housed there.

“It was this clear case of people going online, playing games and doing things together,” Driscoll said. “But it was by way of the pre-existing relationship that we all had.”

Many years later, as he took on “The Modem World” project, Driscoll learned that online communities such as his built around Dungeons & Dragons were common during that time.

“I really focused on these small-scale, dial-up bulletin boards,” he said, “and there were over 100,000 across North America. Every single telephone area code had at least one at one time or another, and some had hundreds.”

Communities were formed through niche interests such as Dungeons & Dragons and the rock band the Grateful Dead.

“Grateful Dead fans were big early adopters of the online world,” Driscoll said, “in part because they had pre-existing networks for sharing rides to shows and trading tapes and building databases and things. And you can see the legacies of that period in the overwhelming amount of information about the Dead that’s online now.”

Driscoll said an important constituency in the early online world was the gay and transgender community.

“Depending on where someone lived, they may not have been connected to a big community or they may have been trying to find some space or find a place where they could be private online,” he said. “So there were large, lively networks of queer people that unfolded in different parts of North America by way of these dial-up networks.”

While online communication today looks drastically different, some elements remain. Children of the ’90s might remember using America Online’s Instant Messenger feature to chat with friends. If you squint now “and step back,” Driscoll said, “Facebook looks a lot like AOL. You have a buddy list, you can IM people, you can see who’s online. It’s very similar.”

The grassroots way of drawing people together online with similar interests has been lost, however.

“Now, we rely on search engines or recommendation algorithms, built into these social media systems, that direct us to further explore certain interests,” Driscoll said. “There are benefits to that and there are drawbacks, too, in part because a lot of those systems are not transparent about how they work, or they may not be organized to serve the creation of healthy communities. They may be organized to keep you online longer or keep you coming back.

“The purpose of building online systems was really different in the era where many of them were run by amateurs and hobbyists, to now where they may be beholden to large venture capital firms.”

Learning about the origins of social media can tell us a lot about the future of the medium, Driscoll said.

“Things change,” he said. “There was a time when AOL was absolutely dominant, and now we live in a post-AOL time.

“Many people are trying to imagine what the future is going to look like. But they don’t need to imagine it from scratch. Books like mine, and those of my colleagues, are documenting efforts to build other internets under different conditions with different sets of values and different norms and different technologies, different economics. And we can use these histories as raw materials for imagining a better future for our internet.”