The Sound of Music, Composed With Disability in Mind

Molly Joyce has found an instrument that enables her to embrace her disability, a vintage electric toy organ.

Molly Joyce was in sixth grade when she started composing music and experimenting with musical notation software.

“It was like a game,” she said, “combining the music in my head with the software and playing it back.” She could change the notes, the timing, and make other special effects.

Now a first-year doctoral student in the University of Virginia’s composition and computer technologies program, Joyce said learning to play an instrument usually comes before composing music, but her journey involved learning both at the same time.

“Writing music is the easiest and hardest thing I know how to do, and for me has been continually informed by life experience,” she said.

Joyce’s life experience took an unexpected turn when she was in a car accident at the age of 7 that nearly amputated her left hand. No one else in the family of four was seriously injured. Doctors saved her hand, but were not able to restore the dexterity that once flowed through her fingers.

Joyce, who attended the Juilliard School and Yale University, is pursuing a doctoral degree in the Music Department’s composition and computer technologies program.

That did not stop her from eventually pursuing music as a career. But it took years for her to acknowledge that the disability she lives with is a fundamental part of who she is – and instead of trying to cloak it, she could use it to stir creativity in her compositions.

“My journey went from completely denying it, to questioning ‘Why did this happen to me?,’ to [going through] a gradual process until I felt the joy of discovering more of my artistry by working with my disability,” Joyce said.

This fall, she released her second album of experimental music, “Perspective,” which includes tracks with the voices of people with disabilities. She asked them a series of questions, such as “What is weakness for you? What is resilience for you? What is interdependence for you?”

Joyce selected some of their comments and composed background music using what has become her favorite instrument – an electric toy organ that she bought on eBay while in college at the Juilliard School in New York City. It’s no longer made, she said, calling it “vintage.” She plays the keys with the fingers of her right hand and pushes the chord buttons with the side of her left hand, because she can’t move those fingers.

Although Joyce took violin lessons and played the piano before the accident, the limited movement in her healed left hand meant she would have to reshape how she pursued music.

After a car accident in which she nearly lost her hand at age 7, Joyce learned to play instruments adaptively, but then turned toward composing music.

“I just remember a lot of surgeries and physical therapy,” she said. Her mother, a doctor, looked for specialists and even took her out of state (they were living in Pittsburgh at the time).

“A physical therapist helped me a lot with getting back to playing music,” Joyce said, and she learned to play the cello and trumpet adaptively, the latter into high school.

She said her parents did a lot to distract her and make her feel better, but they also pushed her to persevere. Joyce joked that her mother’s desire for her to be involved in music backfired, because now she’s taken it so seriously, it’s become her career and her passion.

She majored in composition at Juilliard. She then earned a master’s degree at Yale University’s School of Music, and for the past five years has been traveling around the country and the world, taking on residencies and artist fellowships. She was asked to speak at TEDx MidAtlantic in 2017.

As she studied composing, she realized she didn’t have to think about what her hand could or couldn’t do, she said. Composing also gave her outlets – she composes pieces on commission and collaborates with musicians and artists.

Joyce recently released her second album of experimental music, “Perspective,” which includes tracks with the voices of people with disabilities, as well as her electric toy organ.

Her work has been commissioned and performed from Carnegie Hall to the Midwest, from Stockholm to the Sydney Opera House in Australia. In early December, she performed in Belgium and then gave a talk in the Netherlands.

For a long time, she was skeptical of ideas about the artist’s role in society and about being a disability activist, she said. To her, it felt forced sometimes, like it was telling listeners what they were supposed to hear.

At Yale, she took a course that changed her mind. “Music, Service and Society” examined the relationships between art and education, social change and democracy. The more she learned and thought about it, the more she considered how her disability influenced her and her experience with the world.

“For me, the course prompted me to look inward – to think about my role in society, what I could offer as an artist.

“When I discovered disability studies in graduate school, I started thinking about the social model and social constructions of disability – like if there’s a lack of elevators or wheelchair ramps for accessibility, not putting it on the individual, but on society.”

Wanting to explore the topic further, Joyce completed an online certificate program in disability studies through the City University of New York. She explored how she could perform with her small electric organ. “I still get nervous, but I love performing,” she said.

“Music overall is very physical; not just playing an instrument, but the ways it becomes manifest – music is made of sound waves that vibrate in your body and we hear with our eardrums. When composing, I try to feel the music in my body, feel the flow of it.

“I became more comfortable embracing my own physicality, realizing this is natural for me,” she said.

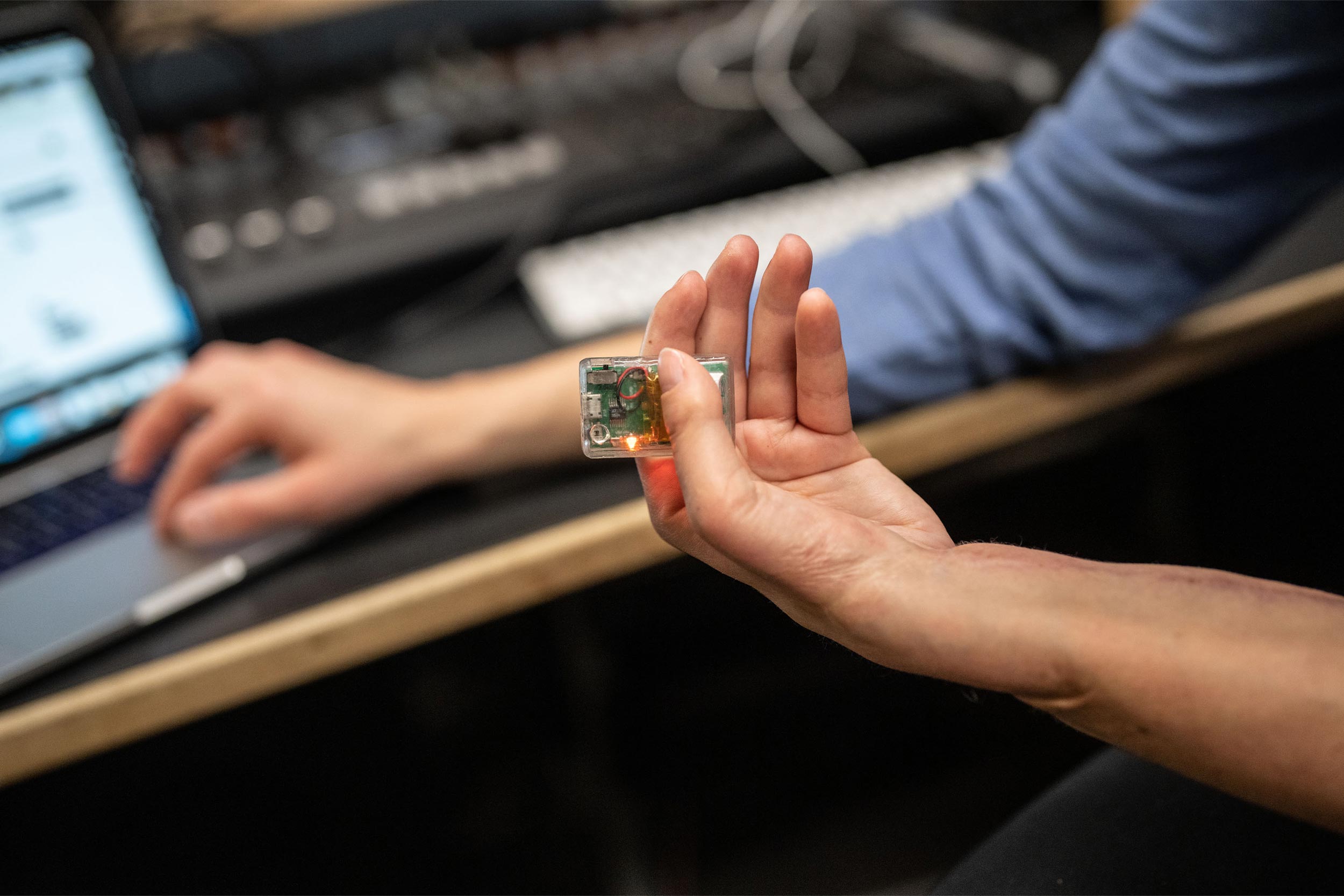

Joyce is experimenting with a new kind of motion sensor, called Mugic, for music, dance and theater professionals that can turn movement into sound.

Joyce described her first full-length album, “Breaking and Entering,” released in 2020, as her personal reckoning with having an acquired disability, describing her lyrics as abstract, not direct but metaphorical.

The new album, “Perspective,” resulted from a project she began in 2019 after well-known disability rights activist Judith Heumann, whom Joyce considers a mentor, challenged Joyce to be direct about her disability, noting that Joyce didn’t mention it in the bio on her website. She said if people don’t talk about their disabilities because they’re worried about the stigma, that creates more stigma.

“Years later, I can say I don’t care what people think, but I was afraid people would think it [the emphasis on disability studies] was coming out of nowhere compared to my previous work.

“‘Perspective’ shows a more intimate view of disability,” Joyce said, where she presents people’s voices and perspectives firsthand, instead of someone else’s external narratives about them.

She has received rave reviews for this latest work and from her UVA professors, too.

Ted Coffey, who chairs the Music Department and also works with computer technologies, described her work as “exceptionally well-considered – in terms of instrumental and other media resources, technical means and affective character. She composes spaces for others to be heard and seen and felt.”

Her faculty adviser, JoVia Armstrong, said, “I feel like I’m learning more from her than the other way around. Through our conversations, Molly has been taking me deeper into the lens of what it means to have a disability and how its meaning is different from person to person.

“Her music is quite compelling as well,” said Armstrong, an assistant professor who joined the music department this year. “It seems to make you focus on the words of disabled people about their meaning of disability. Just hearing their answers makes you think deeply about how much we as able-bodied folks in society take for granted.

“Her work ethic stands out as a student with very strong goals. She is highly determined,” Armstrong said. “She’s really on top of her game.”