‘A Restless, Revolutionary Book’: Jefferson’s Work on Virginia Lives Online

If Thomas Jefferson had access to modern word processing, people today might not have the chance to see his mind at work as they do now with a new Web application dedicated to the University of Virginia founder’s only published book, “Notes on the State of Virginia.”

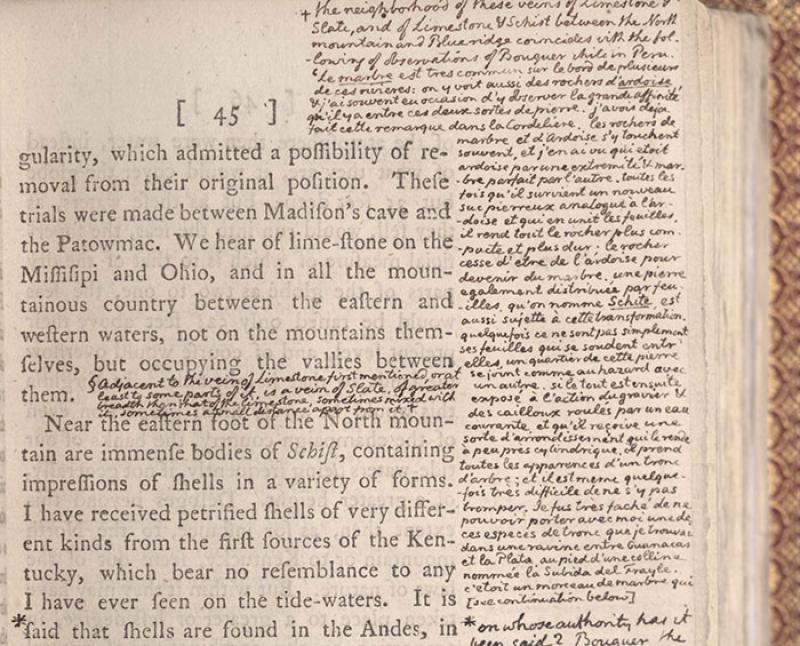

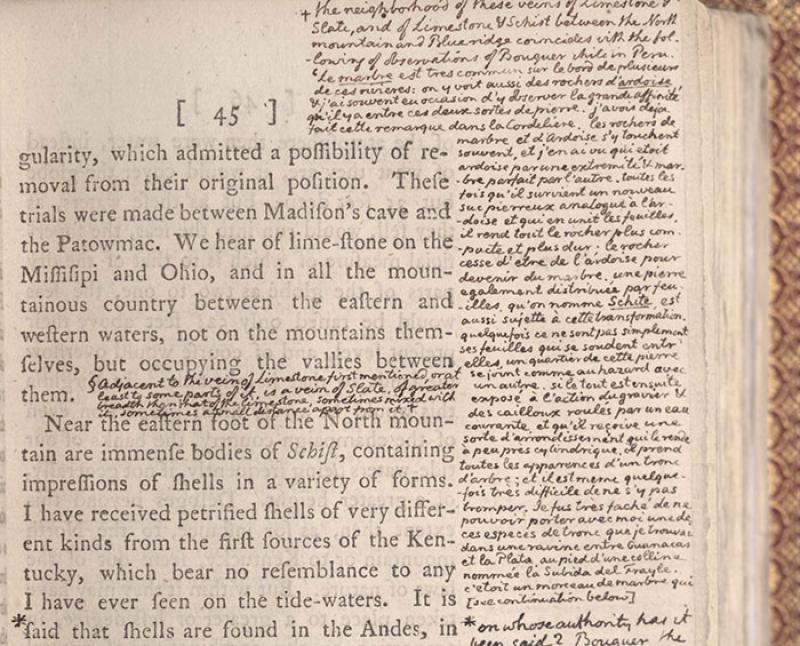

If he had Microsoft Word as he revised the “Notes” from 1784 throughout his life, Jefferson would likely have cut and pasted his changes in a computer file, adding and deleting passages, leaving no traces of his thought process. Instead, he wrote in the margins of his own printed copy, which is preserved in U.Va.’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Those notes were incorporated into a later edition printed after his death.

The new “Notes” Web application – developed by U.Va. English professors John O’Brien and Brad Pasanek, with the help of students and the University Library’s Scholars’ Lab – includes two versions of Jefferson’s encyclopedic volume: one of the first 1784 printings, which he gave to the Marquis de Lafayette, and a 1787 copy whose pages are full of his handwritten annotations, revisions and personal thoughts. The Web app presents their third edition in a high-quality, readable, searchable form that can be used on any electronic device.

Each section of the book addresses a question about a subject or group of topics, such as natural history, climate, inhabitants, politics, religion and commerce. Jefferson incorporated tables and lists, and also a map of Virginia.

Visitors to the application see the list of sections under the heading “Milestones.” After clicking on a link – say for “Climate” – the user can read the modern version and click on images of the 1784 and 1787 versions, plus link to the marginalia Jefferson added, to read his handwriting.

“

The book is so valuable that it is one of Special Collections’ very few “restricted” holdings. Via the application, “Notes on the State of Virginia” has the potential to reach many more people, Pasanek said, allowing students and scholars to consider the changes Jefferson made and why.

Jefferson wrote the book in response to a 1780 questionnaire from François Marbois, a French emissary to the Continental Congress. Although Marbois gave the 20 questions to representatives in all the first American states, “only Jefferson seized the opportunity to write a detailed and comprehensive account of his native Virginia,” O’Brien and Pasanek write in their introduction.

Others gave brief accounts of their states, as if filling in the blanks, O’Brien said. Not all of the responses exist, with some lost or perhaps never written.

As the commonwealth of Virginia changed or as he read something new, Jefferson recorded those changes, added new facts and observations or even scratched out notes. For example, after Jefferson read naturalist William Bartram, who in 1791 published an account of his travels in Southern states and territories below Virginia, Jefferson added quotes to his book.

“It’s not like any other book. It’s not a narrative history,” O’Brien said. It’s more like a personal encyclopedia.

Jefferson knew the state would change and keep on changing, said Pasanek, who described the work as “restless.”

Even his choice of the phrase, “the state of Virginia,” was most likely an intentional pun – not only meaning one of the new United States, but also a temporal condition.

“Radical that he was, he knew it couldn’t be fixed in print. Just as he kept changing his house, Monticello – he would build something, tear it down and build again – he would work on the book,” Pasanek said.

“He’s living and working in a moment of change, and it’s not clear to him how to convey what he wants to convey with the technology available to him,” he said. “That’s similar to where we are now.”

Pasanek, who describes himself as a “digital humanist,” had his class on the literature of slavery closely read sections of the “Notes” and then consult Jefferson’s marginalia, and O’Brien intends to include the application in an upcoming graduate-level class. Colleague Jerome McGann, an award-winning pioneer in digital humanities, is currently using it in a graduate class.

O’Brien and Pasanek dove into the project almost three years ago, seeking to make a high-quality, readable text that students could use in a variety of classes, they said. The Jefferson Trust backed the project with seed money.

At first they envisioned it as a mobile app to be available from Apple, they said, but the company has its own definitions of what a book is and what “interactive” means, and rejected the project several times. Pasanek and O’Brien described what happened in an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education a year ago.

Going back to the drawing board, they turned to Wayne Graham and Jeremy Boggs of the Scholars’ Lab to redesign it for another digital medium, the Web.

Graham, head of research and development, said he and Boggs put a great deal of thought into how they wanted and expected users of this application to interact with the text.

“We wanted to build a system that was not constrained to a particular platform, that allowed readers to focus on the actual text, and allowed us to layer interpretive elements (footnotes, images of the two editions and marginalia) for users to interact with,” he wrote in an email.

“We were reliant on the kindness of staff from the library and the lab,” O’Brien said. “Everyone felt that U.Va. had the responsibility – that if anyone was going to do this project, it should be U.Va.”