Peeking Under ‘Doomsday Glacier,’ a Dripping Timebomb

The University of Virginia has collaborated on new underwater research that has found something additionally disturbing about the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica – aka the “Doomsday Glacier,” so named because it holds the fate of our coastline in the balance as it acts as a gateway to the larger West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Its mass may change in relatively rapid bursts, and faster than satellites have warned.

Lauren Miller Simkins specializes in geological research related to glaciers.

If the glacier untethers during one of these bursts, sea level might rise as much as 10 feet over the coming centuries.

“This glacier in particular is capable of retreating twice as fast as we previously thought from satellite data alone, so it may be poised for larger retreat events,” said Lauren Miller Simkins, an assistant professor of environmental sciences and a coauthor of the research that was published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“Retreat,” unfortunately, isn’t the hopeful term it might otherwise be. It refers to loss of ice mass once sitting on land. And when large sheets of ice retreat, the added water to the ocean raises global sea level and can inundate shores great distances away.

The East Coast of the U.S., including Virginia, stands to be particularly hard hit by sea level rise sourced from Antarctica, the geology professor said.

Scientists recently asserted that the approximately 75-mile-wide, Florida-sized glacier is melting at its fastest rate in more than 5,500 years. The glacier is already the largest contributor to sea level rise, at about 4% of the ocean’s volume.

The new findings may upend even the current worrisome prediction models.

What Lies Beneath

Imprints on the ocean floor are nature’s way of documenting how glaciers have expanded and retracted historically, providing a fuller understanding than satellite measures alone can provide. Yet getting to them has been difficult.

Icebergs can break off unexpectedly, for example, causing mini-tsunamis that may engulf the crews on research vessels seeking to make up-close observations.

However, by using autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs, equipped with special sensors, the multi-institution research team has recently begun to map more effectively the topography under the glacier.

“It can be a really dangerous place and really difficult to get good observations,” Simkins said. “Being able to use these underwater vehicles is a huge advance – not only for safety, but to get to places under the ice.”

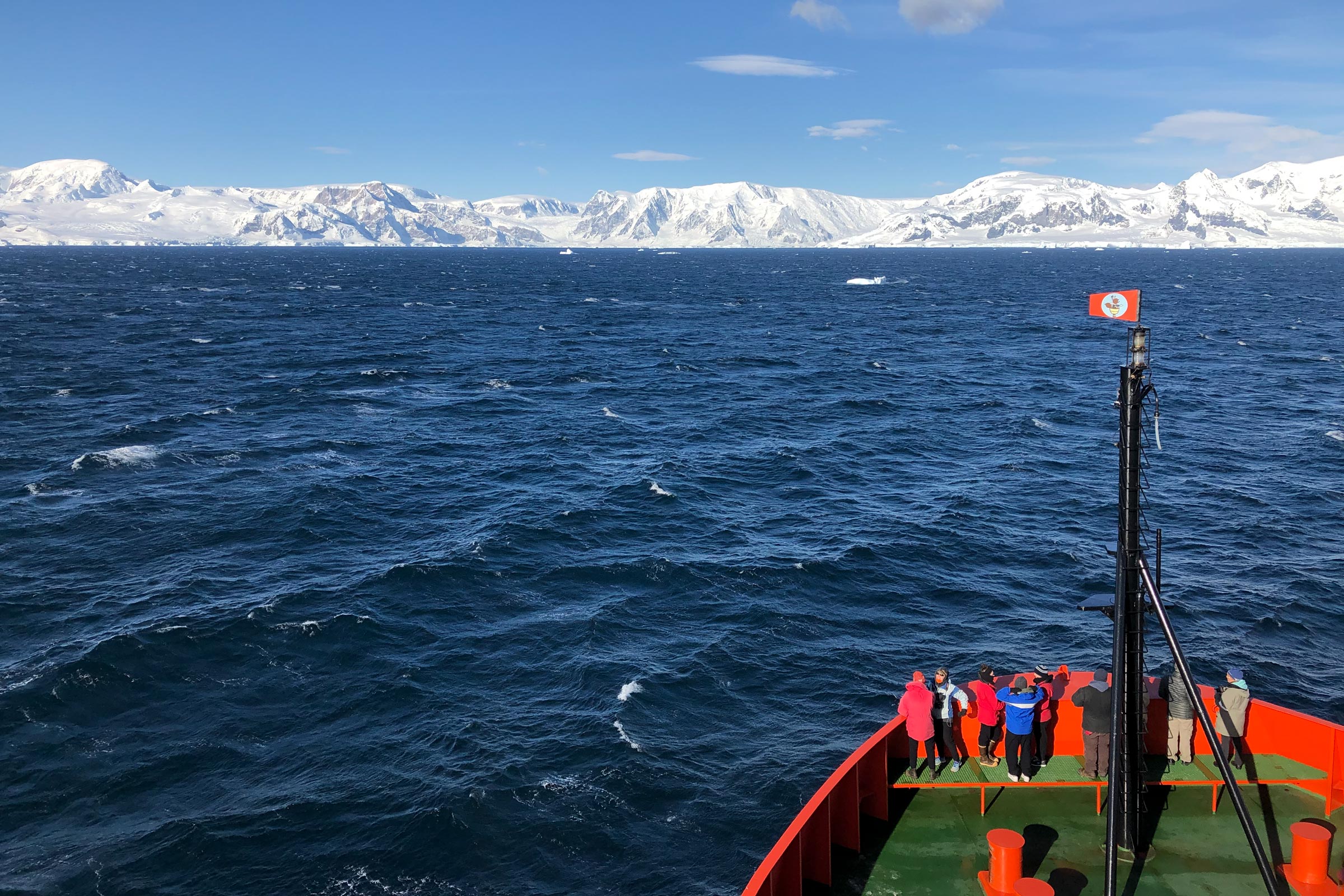

Researchers no longer have to study glaciers from a distance. They can dispatch autonomous underwater vehicles from their boats that can scan the topography underneath. (Photo courtesy Lauren Miller Simkins)

The five-year research project, which wrapped up this year, documented how Thwaites detached from a supporting seabed structure sometime in the last 200 years, rocking and receding with the tides.

The researchers think that the 160 parallel ridges that were formed from the leading edge of the glacier were cast over a period of about six months. At that rate, the retreat would be equivalent to 1.3 miles per year – a retreat twice as fast as any satellites showed in the eight years preceding the research.

“Our results suggest that pulses of very rapid retreat have occurred at Thwaites Glacier in the last two centuries, and possibly as recently as the mid-20th century,” said marine geophysicist Alastair Graham of the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science, the study’s lead author.

Witnessing the Glacier

Simkins’ lab at UVA analyzes data that comes back from the ship. That includes not just numerical data of the seafloor from ship-based and AUV surveys, but also sediment samples dug out from the once ice-covered seafloor.

Simkins has made several trips to Antarctica. The scale of the ice sheet is breathtaking, she said, and hard to capture in a photograph that doesn’t contain manmade landmarks for perspective.

For her, though, the witnessing doesn’t evoke thoughts of doomsday, but curiosity and hope.

“I think of all of the unanswered questions and all the ways we can improve projections of the ice sheet moving into the future,” she said.

In recent years, Simkins’ graduate students are more often the ones aboard the ice-cutting research vessel. Doctoral candidates Allison Lepp, who is investigating the meltwater history of Thwaites, and Santiago Munevar Garcia, who studies the sensitivity of ice streams in subglacial topography, made the trek in 2020.

Doctoral candidates Allison Lepp and Santiago Munevar Garcia made the trip to Thwaites Glacier in 2020. (Photo courtesy Allison Lepp)

The trip involves prolonged isolation in the cold, which is offset by the warmth of scientific camaraderie.

“The experience was exhausting, but invigorating at the same time,” said Lepp, who studies sediment cores. “We worked 12-hour days, seven days a week for two months. Each day was different, and the interdisciplinary expertise on board – including oceanographers, marine mammal biologists and marine geophysicists – created a unique, floating classroom with a variety of diverse perspectives to learn from.”

She said one of the biggest lessons from the experience was the importance of being flexible.

“At any moment we had to be ready to adjust to weather or sea ice conditions, equipment malfunctions, or new and unexpected findings,” she said.

Forewarned Is Forearmed

At UVA, Simkins teaches general courses such as Fundamentals of Geology, as well as more specific ones, such as Polar Environments.

She said Antarctica is a reminder that there are places on Earth relatively untouched by humans, yet which affect us all, and that’s something she wants students in her classroom to think about.

“We’re physically separated from places like Antarctica, but we are connected in terms of changes in sea level and climate,” she said.

Both humans and animals, including emperor penguins who live on the glacier, may be affected by changes to the ice mass. (Photo by Linda Welzenbach, Rice University)

For her students inheriting the planet – and for lawmakers and government officials making key decisions right now – she would stress that to be forewarned is to be forearmed.

As the U.S. government plans for a new research vessel that will replace the two existing ones, which have reached the ends of their lifespans, she hopes that AUVs and other technology not currently planned for inclusion on the replacement ship will be given renewed consideration.

“How can we better outfit our ships to do this new and exciting science?” she asked rhetorically. “There’s some activism that has to take place, and that’s on the part of the scientists who use those technologies and infrastructure.”