How UVA Shaped Georgia O’Keeffe

When Georgia O’Keeffe, now known as a pioneer of American modernism, came to the University of Virginia to take a 1912 summer course for female art teachers, she was still reeling from her parents’ separation and even considering giving up her dream of becoming an artist.

“It was the philosophy of art and empowerment that she learned here that really got her going,” said Elizabeth Turner, a professor of modern art in UVA’s McIntire Department of Art.

That summer – the first time women were allowed to take certain courses at UVA – the 25-year-old O’Keeffe enrolled in visiting artist Alon Bement’s course studying the design philosophies of American artist and educator Arthur Wesley Dow. It proved to be such a pivotal moment that the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico recently dedicated an entire exhibition to it: “O’Keeffe at the University of Virginia, 1912-1914.”

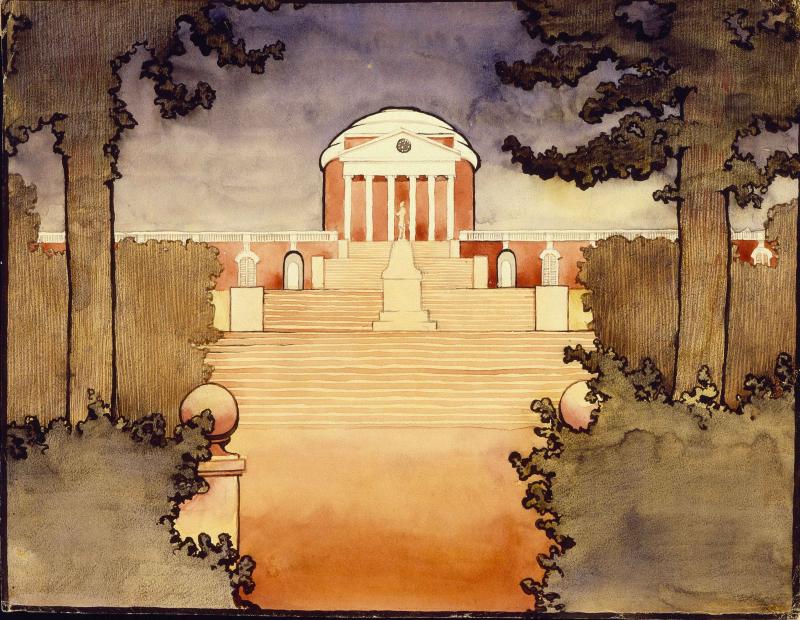

The exhibition, which opened Nov. 4, features watercolors from O’Keeffe’s three summers at UVA, such as the above depiction of the Rotunda. They reflect Dow’s philosophy that art should not be an imitation or copy of nature, but instead personal expression realized through design and composition.

That idea, which ran counter to traditional teaching methods at the time, renewed O’Keeffe’s excitement about art and eventually underpinned the American Modernism movement that she played such a critical role in.

“There was a notebook that she created that was time stamped ‘UVA 1912-1914.’ It showed a single body of work directed at the UVA Grounds, clearly student work guided by the exercises of Dow,” said Carolyn Kastner, the museum’s curator. “Instead of just seeing it as student work, we can now see it as the beginning of the learning curve that led her to abstraction. That makes it really exciting.”

According to Turner, the watercolors show O’Keeffe’s early experiments with design as she carefully uses the trees and other elements to frame her subjects. The watercolor shown at right, for example, depicts a view of the Range rooms flanking the Academical Village, seen from a pathway between two of the Pavilion gardens. O’Keeffe uses trees and other landscape features to create deliberate symmetry.

“In Dow’s teaching, students are taught to make choices and to validate their own choices about dividing and filling space,” Turner said. “It does not teach descriptive drawing, it teaches design.”

Another depiction of the Rotunda has a similarly symmetrical composition, with dark trees carefully framing the building.

“These watercolors have a very centered quality, if you look at where the doors are shown and how there is a kind of keyhole that pinches in and then opens up,” Turner said. “She is deliberately designing this.”

Some of the watercolors can be directly correlated to instructions or exercises in Dow’s book, “Composition.” For example, Exercise No. 34 asks students to create “a landscape, reduced to its main lines, all detail being omitted.”

“That is such a simple sentence, but I think it guided her entire career,” Kastner said. “What we see in these works is Georgia O’Keeffe internalizing that lesson.”

Kastner’s team reviewed each of the watercolors under a microscope and realized that they were created from hand-ground pigments, indicating that O’Keeffe was also learning to create her own pigments and materials.

“This is a fun period in O’Keeffe’s life, because she is learning a lot about watercolor, which she pursues in a very masterful way,” Kastner said. “It is the beginning of a very creative mind imagining what she can do with the skills she is being offered.”

For two years after that first summer, O’Keeffe spent the school year teaching high school and college students around the country, then returned to Charlottesville in the summer, where her mother ran a boardinghouse on Wertland Street. She took courses, painted various sites around Grounds and often ventured out into the surrounding area to camp and hike, inspired by the beauty of the Blue Ridge Mountains just as she would later be captivated by the landscapes of New Mexico.

Her paintings became more and more abstract, and in 1914 she decided to take classes in New York City, where she met and worked with Dow. By 1916, her work was being shown by photographer Alfred Stieglitz (later O’Keeffe’s husband) in his renowned 291 gallery and O’Keeffe was well on her way to becoming a sensation.

“Her work really gained a huge following in her lifetime and still has a huge following,” Turner said. “She engaged people very powerfully on an emotional and psychological level with abstraction, which I would say is her great contribution. And she had to invent it to do it; it didn’t exist at the time.”

For Turner, there is something special about being able to point out to her students that famed artists like O’Keeffe have walked these Grounds.